ASPECTS OF ASPECT

Laura A. Janda

UiT The Arctic University of Norway

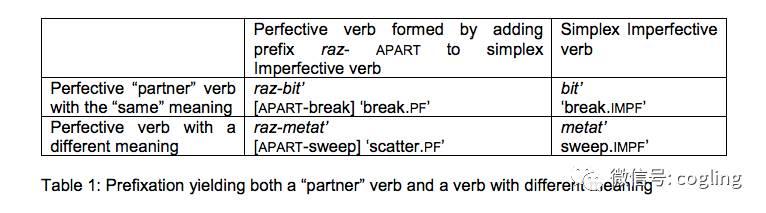

I approach the anatomy of a single grammatical category from a variety of perspectives within the usage-based framework of cognitive linguistics. The category is aspect, obligatorily expressed as Perfective or Imperfective in verb forms in Russian. Russian aspect may look like a simple binary distinction, but the details reveal a phenomenon that requires nearly every tool in our linguistic arsenal. I explore Russian aspect from four angles: semantics, morphology, grammatical profiles, and context. I share numerous remarkable insights that I have gathered in the course of this adventure, which has occupied me for over thirty years. Semantics: One could say that Perfective verbs describe situations as complete events, while Imperfective verbs describe situations as ongoing or repeated processes, but this is a gross oversimplification. Both Perfective and Imperfective are complex and polysemous. They can be motivated by metaphorical mapping from discrete solid objects (for Perfective) and fluid substances (for Imperfective). This metaphor accounts for the full spectrum of uses of aspect,including some relatively exotic uses of Imperfective to express both politeness and rudeness (Janda 2004). Another unusual characteristic of Russian aspect is the range of atelic Perfectives which can be formed from every actional type, even states (Janda 2015). Morphology: A complex system of overtwenty overt morphological markers for Perfective vs. Imperfective has been cobbled together over the centuries from various sources (mostly prepositions).However, many verbs have no overt morphological markers and, due to these gapsplus inconsistencies, overt markers are only about 90% reliable as predictors of aspect (Eckhoff, Janda & Lyashevskaya 2017). Prefixes form the bulk ofthis system, with sixteen of them combining with simplex Imperfective verbs to form nearly two thousand Perfective “partner verbs” with the “same” meaning,plus thousands of other Perfectives with “different” meanings than the simplex verbs (see the illustration in Table 1 for Perfective verbs formed with theprefix raz- meaning APART).

Traditionally the prefixes used to form “partner” verbshave been claimed to be semantically “empty”. However, we hypothesize that the prefixes actually serve as verbal analogs to numeral classifiers, sorting the verbal lexicon according to the types of events that can be composed of variousactions just as numeral classifiers sort the types of discrete objects that can be formed from various substances (Janda et al. 2013, Dickey & Janda 2015).This hypothesis builds on McGregor’s (2002) work of verb classifier systems in Australian languages, and on the metaphorical model of Russian aspect described in the previous paragraph. Grammatical Profiles: Grammatical profiles are therelative frequency patterns of paradigm forms for a word. Perfective verbsbe have differently from Imperfective verbs, a fact that was worked out indetail for the aggregates of Perfective vs. Imperfective verbs in Russian inJanda & Lyashevskaya 2011: for example, Perfectives are more frequent in past tense forms, while Imperfectives are more frequent in non-past (present)tense forms. We turned this analysis upside down to ask whether it is possible to predict the aspect of individual verbs based only on the relative frequency of their forms (Eckhoff, Janda & Lyashevskaya 2017). Remarkably, it is possibleto do so more than 90% of the time. In fact, there is no statistically significant difference between the prediction of a verb’s aspect from the famously complex morphological system described above vs. simply tracking the frequency of a verb’s paradigm forms. Context: Descriptive grammars of Russian list dozens of adverbials and other syntactic “triggers” that indicate aspect with fairly good reliability (around 96%). For example, uže ‘already’ is atrigger for Perfective verbs (Ja uže s”ela banany ‘I already ate the bananas’),while vsegda ‘always’ is a trigger for Imperfective verbs (Ja vsegda ela banany ‘Ialways ate bananas’). But these triggers only work when they are available. We have discovered (Reynolds 2016) that even when all of the known triggers are taken in aggregate, they are relatively rare in actual language use, appearing in association with only about 2% of verbs in corpus language samples. This isa serious problem because textbooks and language courses devote most of their presentation of how to use Russian aspect in terms of such triggers. As linguists and as instructors, we fail to represent 98% of the relationship ofcontext to aspect. And those remaining 98% of contexts conceal many mysteries,both those where native speakers “just know” what aspect to expect (despite theabsence of known cues) as well as those where either aspect is possible,depending upon the construal of the speaker. We are undertaking a series of experiments in hopes of unravelling some of these mysteries.

Traditionally the prefixes used to form “partner” verbshave been claimed to be semantically “empty”. However, we hypothesize that the prefixes actually serve as verbal analogs to numeral classifiers, sorting the verbal lexicon according to the types of events that can be composed of variousactions just as numeral classifiers sort the types of discrete objects that can be formed from various substances (Janda et al. 2013, Dickey & Janda 2015).This hypothesis builds on McGregor’s (2002) work of verb classifier systems in Australian languages, and on the metaphorical model of Russian aspect described in the previous paragraph. Grammatical Profiles: Grammatical profiles are therelative frequency patterns of paradigm forms for a word. Perfective verbsbe have differently from Imperfective verbs, a fact that was worked out indetail for the aggregates of Perfective vs. Imperfective verbs in Russian inJanda & Lyashevskaya 2011: for example, Perfectives are more frequent in past tense forms, while Imperfectives are more frequent in non-past (present)tense forms. We turned this analysis upside down to ask whether it is possible to predict the aspect of individual verbs based only on the relative frequency of their forms (Eckhoff, Janda & Lyashevskaya 2017). Remarkably, it is possibleto do so more than 90% of the time. In fact, there is no statistically significant difference between the prediction of a verb’s aspect from the famously complex morphological system described above vs. simply tracking the frequency of a verb’s paradigm forms. Context: Descriptive grammars of Russian list dozens of adverbials and other syntactic “triggers” that indicate aspect with fairly good reliability (around 96%). For example, uže ‘already’ is atrigger for Perfective verbs (Ja uže s”ela banany ‘I already ate the bananas’),while vsegda ‘always’ is a trigger for Imperfective verbs (Ja vsegda ela banany ‘Ialways ate bananas’). But these triggers only work when they are available. We have discovered (Reynolds 2016) that even when all of the known triggers are taken in aggregate, they are relatively rare in actual language use, appearing in association with only about 2% of verbs in corpus language samples. This isa serious problem because textbooks and language courses devote most of their presentation of how to use Russian aspect in terms of such triggers. As linguists and as instructors, we fail to represent 98% of the relationship ofcontext to aspect. And those remaining 98% of contexts conceal many mysteries,both those where native speakers “just know” what aspect to expect (despite theabsence of known cues) as well as those where either aspect is possible,depending upon the construal of the speaker. We are undertaking a series of experiments in hopes of unravelling some of these mysteries.